KEISE-SHIMA — MARCH 31

On Friday, March 30, I was summoned to a meeting aboard a destroyer in the Kerama Retto. A Navy Captain (with the honorary rank of Commodore) presided. Those in attendance included Navy and Army personnel.

Without preamble, the Captain opened the meeting with the following words: “We’re going on a suicide mission. I don’t care what the Army does, but the Navy is getting out as soon as our job is done.”

By now, the speaker had my undivided attention. What’s all this about? ·1What is he talking about in that calm voice? I was soon to know.

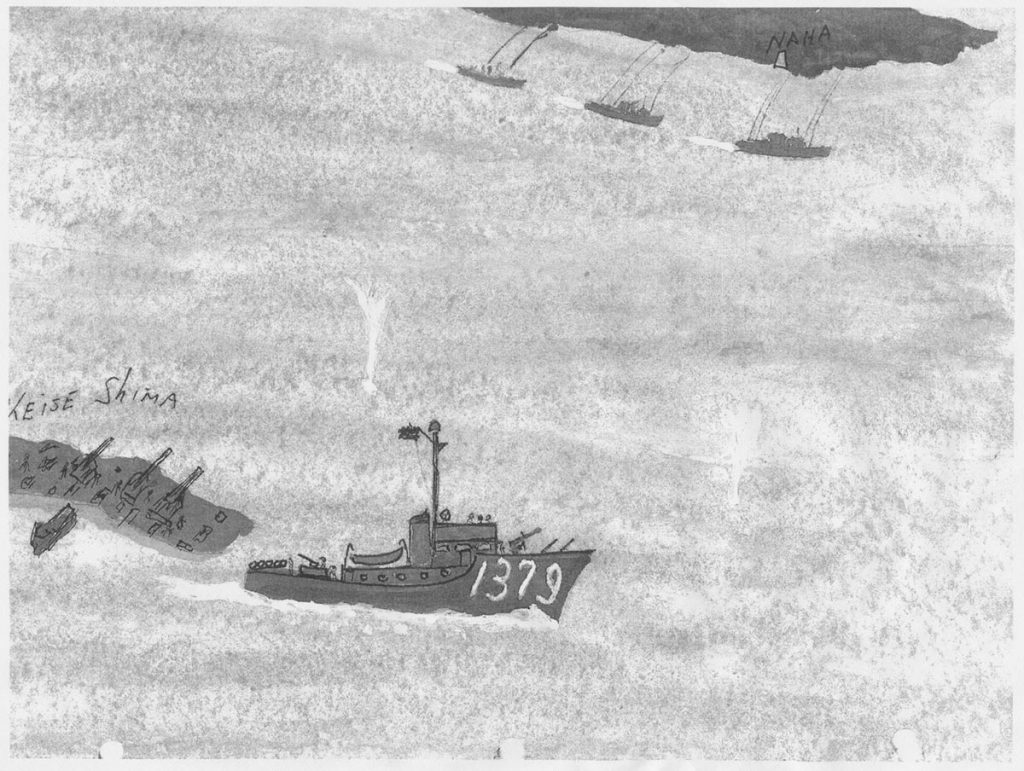

The Captain then outlined the forthcoming mission. At 0330 the next morning, a small number of amphibious vessels, transporting Army personnel, guns, food, and other supplies, would depart Kerama Retto and sail east to the Keise-Shima, the sandy islets 6 miles off the west coast of Okinawa. Our group of amphibious craft, accompanied by patrol vessels, would proceed at about 7 knots, so as to cover the 14-mile run from Kerama Retto to KeiseShima in about 2 hours, thus arriving off our target at about the end of morning twilight. Morning sunrise would be at 0632. Landing operations would then take place, and the Army would set up their field guns and other gear on the islets.

The Captain then discussed the tactical basis of this operation. The guns to be used would be 155mm, to be manned by the Army artillery teams. There would be 4 batteries, i.e., a total of 12 of these heavy field pieces, placed on the islets. The precise reason for using these 155’s became clear when the Captain stated that they had a range of 25,000 yards—over 12 miles. The distance from these islets to Naha, the capital city of Okinawa, was about 12,000 yards—about 6 miles. Therefore, the shells fired by these 155’s would not only reach the city of Naha but would land another 6 miles inland. The guns would commence firing on the next day—which was D-Day for the invasion of Okinawa. By use of spotting planes, the guns would interdict any enemy traffic on the roads leading to and from Naha.

Continuing the Captain sketched out the odds: Keise-Shima was unoccupied by Japanese, and we were counting on the element of surprise, that the enemy would not expect us to land on these islets-so close to their shores. Our reasoning was that the Japanese had not worked out artillery coordinates for directing immediate, accurate fire on these islets. But, the Captain added, once they saw us, their powerful coast defense puns-which could easily reach these islets-would try to wipe out this threat to their defense. It was going to be a sticky situation because our forces would be on an immobile target, committed to stay put-without firing these funs until the next morning-for about 12 hours of daylight. During these daylight hours a force of destroyers and cruisers would range up and down the coast between our forces on the islets and the Okinawa coastline, making forays as close to Okinawa as possible so as to draw fire from the Japanese and take the heat off the forces on Keise- Shima.

The Captain concluded the meeting by wishing all good luck. We left the “tin can” and returned to our respective ships, where we briefed our own crews.

MARCH 31

By prearrangement, at O3OO a group of Army artillery staff officers boarded my ship, which was to be the radio control vessel for this operation. We got underway at 0330, joining the other ships involved in this mission. The weather was clear, with calm seas as we headed east. There was no enemy air activity in our area.

Shortly after we had gotten underway, I was joined on the bridge by two Army colonels. We began, over mugs of java, to discuss the forthcoming landing on Keise-Shima. When I voiced my concerns over the coming action, they were quick to fill me in on their views and specialized knowledge.

They had both been in the European theater before winding up in the Pacific. They described—with enthusiasm—the devastating power of the 155’s, nickname, “Long Toms”. “We used them against battle-hardened Germans,” said one of the colonels. “And after we won the day and took prisoners, they asked us about our automatic artillery pieces. We laughed to ourselves at this, because the Germans did not know that the 155’s are not automatic, rather, that it’s the way we set up these guns in batteries of threes: as soon as gun 1 fires, gun 2 fires, then gun 3 fires as soon as gun 2 has fired; as soon as gun 3 has fired, gun 1, which has been reloaded, fires, and so on. Our prisoners were frank to tell us that they were shell-shocked by the terrible destruction of the incoming shells, arriving almost in seconds, one after the other, without let-up. That was the German’s horror: the uninterrupted shelling.”

“Also,” added the other colonel, “as to our estimate that the Japanese will not expect us to land on Keise-Shima, we had a similar situation off the south beaches of France. There was an island very close to the shore—so close that the Germans, with their vaunted thoroughness, had absolutely written off the possibility that we might try to land there—so near to their coast defense guns. But we did land and made food use of that island as part of our invasion, without being killed.”

The next two hours passed by without incident. No enemy air activity was spotted, as we neared our objective. Then, as morning twilight began, we picked up, visually, the low silhouettes of the islets. Our radar had had them on the scope for quite some time, giving me excellent piloting information and very accurate range, but it is always reassuring to a navigator to make a sighting with his own eyes. There were no lights nor signs of life on our target—just as we had expected.

As the sun rose the weather was clear, giving promise of a bright, sunny day. Our amphibious vessels began to close the beaches, and the patrol ships proceeded to their assigned stations around the area.

At this point, the Army artillery team riding my ship began to issue orders to the amphibious craft by use of portable radio gear, manned by a special group of Army communications personnel. This was the common practice during an invasion. My ship had a staggering array of communication equipment—something like 19 transmitters and 21 receivers—operated, during the opening days of an invasion, by a special 10-man team of Navy communications specialists, who would have joined our ship a few weeks before a scheduled operation began. Then, on the evening before, or several hours before H-Hour, a comparable team of Army communications specialists would come aboard with their own portable equipment. About an hour—dependent on conditions—before H-Hour, senior Army officers would then board my ship, station themselves alongside me on the bridge, and, as we drew close—3OO yards or so—to the invasion beach, they had both visual and radio contact with the Army forces going ashore.

Landing operations went along without a hitch, as the Army troops and their equipment and supplies went ashore. Among the supplies landed: water for the use of our troops! After all, there were no wells on these islets, and, even if there were, it was probably too risky to use them.

As I recall, all landing activities were completed by about 0900. Everything was quiet, no sign of any enemy activity. Visibility was excellent, and, as I looked to the east at the coastline of Okinawa, I could see the lighthouse at the entrance to Naha’s harbor. As a piece of piloting data, the distance from the islets to this lighthouse was 12,500 yards—or about 61 miles. The lighthouse appeared as a somewhat squat cylindrical gray tower. I could see something else: our valiant destroyers and cruisers steaming up and down past Naha, firing enormous volleys of shells at enemy gun emplacements in and around the city. Our intrepid ships, I realized, were deliberately moving in very close to the Okinawa shoreline so as to entice return fire and thus distract or delay the shore batteries from firing at us on Keise-Shima.

The morning went by slowly. We had not anchored and we were cruising at trolling speed off the south tip of the southernmost islet, maneuvering in and out, on various courses and without any set pattern, close to the islets’ shores. By now, most of the landing craft had accomplished their tasks and had departed. There were one or two of these landing craft still pulled up on the beaches for last-minute chores. And one landing craft—like us—was cruising slowly back and forth nearby. Then, out of the corner of my eye, I saw this landing craft’s stern beginning to bubble up, a sign that it had begun to speed up. Within seconds, I saw a large plume of water near that craft. Artillery shells! The Japanese had begun to pay attention to us. We came to full General Quarters and began to increase speed and to resort to what we hoped would be evasive tactics—such as radical course changes every couple of minutes—designed to confuse the Japanese coast guns. For the next two or so hours, we were subjected to random shelling, which, I was delighted to observe, did not hit my ship nor any of our forces on the beaches. We could tell—even though we were not experts on artillery fire—that these shells were artillery shells, landing in an obviously high trajectory rather than in a “flat” ricochet: each time, there would be that high plume of water, no detonation, then, the water would quickly subside and the surface revert to its calm appearance.

A Gaelic poet has said, “The heart that sorrows too long turns to stone.” Well, our ship was in somewhat the same situation: our principal weapon, a 3”50 mounted on our forecastle deck, didn’t have the range to fire even half-way toward the coast of Okinawa. We simply had to stand by and hope for the best.

Accordingly, we came to modified General Quarters and began to serve noonchow, on a watch by watch basis. After noon meal had been served, we noticed that the shelling had subsided. For the next few hours only a random shell came over toward us every half hour or so.

The afternoon wore on, and, after what seemed an eternity, our ship was given orders, about 1600, to break off and return to the Kerama Retto. We had been on station off these islets for about 11 hours. I was too tired to remember that the Navy Captain had said, at the meeting the day before, that the Navy was “getting out as soon as our job is done.” Well, the job assigned to my ship had lasted a very long time! But, we had been supremely lucky: our ship had not been hit despite the hundreds of Japanese shells fired at our area; and our plucky Army boys, marooned on those islets and unable—like us—to return to the Kerama Retto, had been equally fortunate. As exhausted as we were, we realized that we had not been spared because of poor Japanese gunnery, rather, because of the splendid and heroic efforts of our larger ships-the destroyers and cruisers-exposing themselves to fire so as to save our operation at Keise-Shima.

That night, we anchored in the Kerama Retto. Although we should have been still geared up from the tensions caused by our close calls off Keise-Shima that day, and, indeed, unable to sleep because of the knowledge that tomorrow morning would be D-Day for the invasion of Okinawa and that our ship would be involved, those not on anchor watch turned in and slept soundly—I know that I did! This is not to portray myself as some sort of hero, devoid of fear. I had plenty of fear. But, in any situation of danger for my ship, I adopted the following attitude: is the ship O.K.? If so, let’s get on with the job. I spent no time afterwards in conjuring up the terrible things that might have happened, rather, tried to imprint in my mind the lesson learned from the event. I took my command responsibilities very, very seriously, trying to merit the “special trust and confidence” which the Navy places in Commanding Officers of its ships. My Navy career during WWII was somewhat unusual, in that I had had uninterrupted command and for almost 3 years. Because I had never served under anyone aboard my ships, I had to learn by experience and by my mistakes. My ships had encountered the expected perils of the sea and the dangers from enemy action. We had survived near-collisions on dark nights while running convoys; had ridden out not only bad line storms but the vicious typhoon off the Palaus in 1944. We had a narrow escape from a twin-engine Japanese bomber, which had “snuck” in low over the water so as to avoid radar detection and suddenly flew over the island mass and swooped down on us as we were trying to guard a crippled destroyer sitting helplessly in a floating drydock at Kossol in the Palaus. One of our closest calls happened in Leyte Gulf in the Philippines. We were about to anchor in 37 feet of water. As we dropped anchor, I ordered the engines cut in astern for an instant so as to get good holding on the anchor. Our screws kicked up a wash and, as I looked down from the bridge, I saw a Japanese mine—about 36 inches in diameter pop up beneath our stern and float within inches along our port side until it passed our bow. Luckily, there were no “horns” projecting from its spherical surface, otherwise the mine would probably have detonated against our ship’s side.