KERAMA RETTO AND KEISE-SHIMA: SPEEDBOATS AND LONG TOMS

by Edward U. O’Donnell

PILOTING INFORMATION

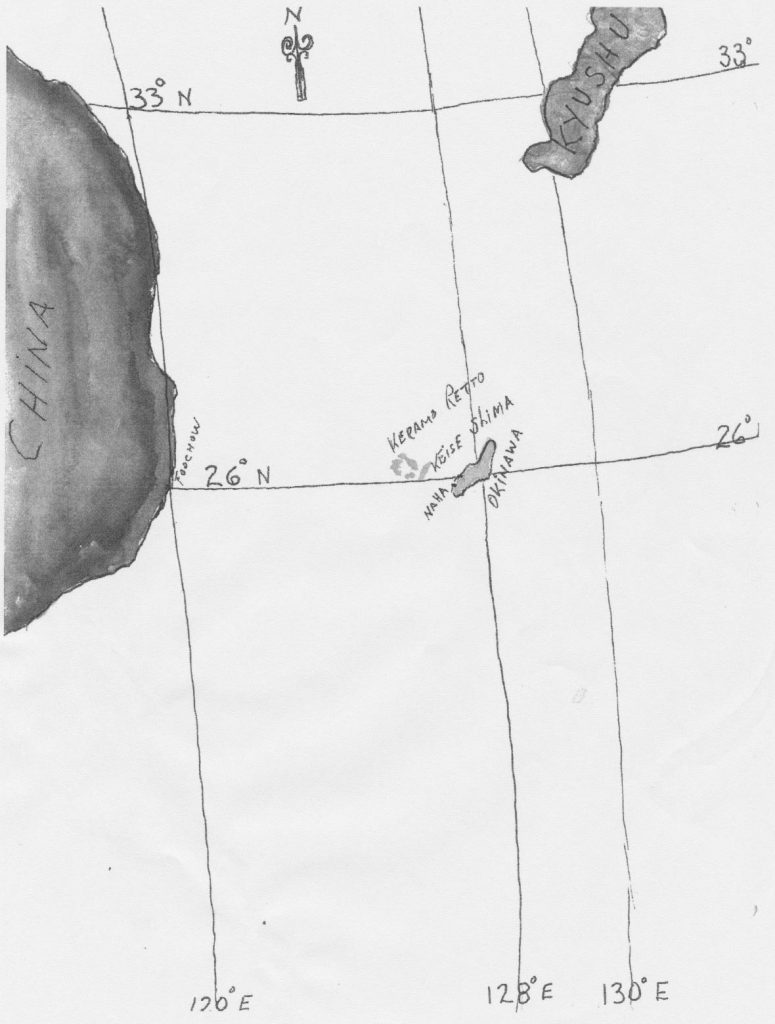

It might be appropriate, at this point, to provide what I might term, “Piloting Information” about the Kerama Retto, Keise-Shima, and Okinawa. In the order of events,

Kerama Retto

A cluster of several small islands, with shelving beaches and interconnecting deep-water channels, located about 20 miles to the west of Okinawa.

Keise-Shima

A group of low, sandy islets (the largest being about 900 yards long) located about 6 miles west of Okinawa’s western coastal capital city of Naha.

Okinawa

The main (60 mile-long) island in the Ryukyu Islands group, located about 350 miles southerly from Kyushu, the southernmost island in the Japanese homeland.

A SCENARIO

The best way in which I can portray the sequence of events described herein is to offer the following scenario: Suppose, if you will, a hostile force intent upon the invasion of the mainland of Cape Cod, Massachusetts as a principal target. The invasion force sails toward the vicinity of Cape Cod’s south beaches, but, in fact, to the consternation of the Cape Codders, who are geared up for an imminent invasion of their beaches at, perhaps, Falmouth or at Hyannis, lands, instead, on the Cape’s off-shore island of Martha’s Vineyard, seizing that island and then occupying an islet about 6 miles off the Cape’s south shore before beginning the assault on the true invasion objective, the mainland of Cape Cod.

This was, essentially, the U.S. strategy for the invasion of Okinawa: our segment of the overall invasion fleet sailed from Leyte Gulf in the Philippines for about 1100 miles in a northerly direction toward Japan. Arriving, at the Kerama Retto island group, about 20 miles to the west of Okinawa on March 26, our forces first invaded and quickly captured that island group, then moved closer toward Okinawa, taking and occupying, on March 31, the small sandy islets, called Keise-Shima, located about 6 miles off the west coast of Okinawa—all as a prelude to the main invasion of Okinawa on the following day, April 1.

MY SHIP – U.S.S. PCS 1379

In March, 1944 my ship, built by L’/heeler Shipbuilding Corporation, Flushing, Long Island, N.Y., was christened by my late first wife Florence, Lord rest her. Shortly before the planned ceremonies, I learned that the wife of a naval officer stationed at 90 Church Street, New York City-3rd naval district headquarters, had been picked to christen the ship. I remember saying to both the naval and shipyard brass that most of my crew and I were superstitious Irish men, and that, if my wife didn’t christen the vessel, we were going to feel very uneasy about the whole affair. The brass deferred to the Gaels.

In March, 1944 I commissioned my ship at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. My command, a wooden hull vessel 136′ in length, with a beam of 24’ and a draft (fully laden) of 7’6″ forward and 9’6″, displacing 323 tons, was a sturdy vessel.

Equipped with twin “straight eight” diesels for main engines, with a cruising speed of 12 knots (and a flank speed of 14 knots) and an economical cruising range of 3,700 miles at 8 knot speed, the ship was outfitted with excellent radar, sonar, fathometer, gyro, and radio gear, together with a water evaporator. Armament consisted of a 3″50 single gun mount on the forecastle deck, a 40mm gun, mounted in a gun tub aft, 4 batteries of 20mm guns, 300-pound depth charges on twin racks on the fantail and on K-guns mounted on either side, together with 16 64-pound rockets (“Minnie Mouse”) mounted on elevated rails on the forecastle deck forward of the 3″50 gun.

Ship’s complement included 100 men and 4 officers. Accommodations for messing and sleeping were somewhat crowded. The ship delivered to the Navy by Wheeler Shipbuilding was to prove to be sound and seaworthy in every respect, and the loving workmanship put into the vessel was evident to all of us. Acceptance, by the Navy, was on an unconditional basis, there were no deficiencies, and, upon acceptance, the vessel was (to quote the ancient, solemn Navy phraseology) “in all respects ready for sea” and it proved to be the case.

Reserved until now are my comments and appraisals of my officers and crew. Based on my experience, it’s great to have a spanking new ship, with all kind: of brand-new equipment, but, what makes the ship is its crew and officers: with a good crew one can make a broken-down hulk function.

The officers (Lt. Pete Fry, Executive Officer; Lt. Bill Cathey, Engineering Officer; Lt.(j.g.) Earle Vickery, Gunnery and Supply 0fficer) who, like me, were all naval reserve officers, were all dedicated to their duties, with a special understanding for the problems of a large crew crowded into cramped quarters, with virtually no privacy.

Our Chief Boatswain’s Mate, Dom Spagnuola (who was one of the few regular Navy men aboard) ensured that all went well topside; while Chief Motor Machinist’s Mate Joe Ward made good on his promises that all engines and auxiliaries would work. Neither would ever fail his ship.

The crew was a truly great group of individuals, hailing from all parts of the U.S. They were welded together in a tight bond, showing a tolerance that would have satisfied any critic. (They literally babied our oldest crew member, Pharmacist’s Mate, lst class “DOC” Eller, an ancient of…39 years) All hands-officers and men- gave uniformly high performances and total loyalty The best encomium which I can give them is that I would be honored to serve with them again-any time, any place.

After a brief shakedown off New York, we were ordered to Miami, Florida, where, at the U.S.N. Subchaser Training Center, we would be put through the paces by the Center’s eagle-eyed training staff. We had to demonstrate, to their satisfaction, our proficiency in shiphandling, navigation, gunnery, and the proper use of our sonar and radar, together with the other disciplines to be expected of any ship passing their scrutiny. (The Commanding Officer of this Center was Captain E. F. MacDaniel, U.S.N., who-as he put it-“was cast up on the beach” after his command, a destroyer, had been sunk by a German submarine. He was-and I say this so many years later one of the most truly revered officers any of us had ever met during our time in service. Two quick comments about our beloved Captain “Mac”: After he had commissioned the Subchaser Center (I had “graduated” in one of the first classes in ’42) he made it a standing rule that any of his subchaser skippers who had some kind of problem was to telephone him directly, using, as the opening words, “This is one of your boys…” Ruthlessly, and , perhaps, in violation of sacred “Chain of command” principles, dear Captain Mac would have the problem solved in about 2 hours- I know, because I availed myself of his very kind offer twice in my career, and the “way was made smooth” before the hour—not the day—had ended. Captain Mac’s office was on the second “deck” of the former warehouse building on Pier 3, on the inner edge of the Miami ship-channel. Every afternoon he would look out his window and watch the “school-ships” (subchasers) carrying the student officers back after exercises at sea stand in the channel and approach the pier. One skipper had the habit of zooming in at knots and, as the ship was directly below Captain Mac’s office, backing down hard so as wind up about 10 feet short of the stone quai wall ahead, making a very “flashy” landing as the ship would stop dead in the water, the mooring lines would be heaved over, and the ship alongside-all for the edification of the student officers aboard. Captain Mac did nothing about this, saying, to his staff, “He’s the skipper. But some day his main engines may not respond in time, and his stem will be about 20 feet up on Biscayne Boulevard. If that happens, I’ll yank him and put him back in school as a student. “And, sure enough, one day, that happened, and the Center had an extra “student.”) Note: after so many years have passed, I look back at the magnificent achievements of Captain Mac, who never did want a shore-going assignment-he wanted to be at sea, sinking German subs-but, he had gritted his teeth and had devoted himself to training subchaser skippers, in the hundreds, and had made his distinguished mark on all of us skippers who had been so fortunate t0 have been under his magic spell. How I wish that I had had the…grace to send him a letter, telling him of his great leadership and of his inspiration to a reserve officer who was “one of his boys.”

After a shakedown at the Fleet Sound School at Key West, working with “tame” subs, we spent the next couple of months in the Caribbean (Cuba, Curacao, and Trinidad-where we operated with “tame” submarines in the Gulf of Paria) and off South America (British Guiana) on escort duties. We were ordered to proceed through the Panama Canal to San Diego, where we joined a group of other vessel and headed for Pearl Harbor, arriving in June, 1944.